English (like all languages) changes a lot based on context. The language you use when texting a friend is different than how you’d write in a job application cover letter. For writers, understanding how to shift the way you write based on context is part of the job. Anyone creating content for the web therefore ought to have a decent understanding of internet language.

Understanding how internet language works doesn’t mean every form of it is appropriate for every context. You probably don’t want to use the language of LOLcats for your business blog (“I can has…SaaS product?” doesn’t really work, does it?). But understanding the norms of internet language, how people are using them, and which linguistic trends your audience recognizes is valuable.

The linguist Gretchen McCulloch has analyzed the crap out of trends in internet language and shared her insights in Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language.

Here are a few useful takeaways for professional content writers.

Conveying Tone Over the Internet

Have you ever sent an email message that sounded calm and polite in your head, but realized belatedly that it read as angry to the person on the other end? Tone is tricky in online writing, and it’s made trickier by the fact that people of different generations and online habits have different norms around internet grammar.

The Passive Aggressive Period

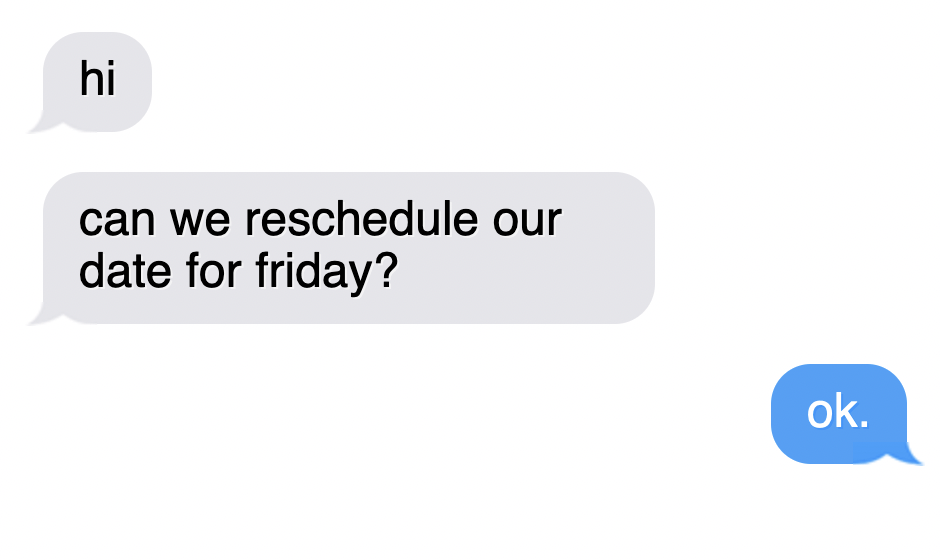

Take, for instance, the passive-aggressive period. For younger generations, the way you use a period over texts or in chat apps can convey that you’re upset about something. Take a look at this interaction:

Depending on your online habits, the respondent here is either simply agreeing to reschedule, or sending a not-so-subtle signal that they’ll do it, but they’re not happy about it.

The passive-aggressive period is one form of typographical tone of voice, and a good example of one that can get you in trouble if you’re communicating with someone who has different norms than yours.

For copywriters, this use of the period won’t apply to most forms of writing you’re likely to do. But as brands start to use chatbots and messaging apps more often, anyone writing copy for them will need to be thinking about the norms of how people talk in that context.

All Caps Shouting

Even if you’ve never encountered the passive-aggressive period before today, you’ve definitely come across other forms of typographical tone of voice. For example, WHAT KIND OF PERSON EVEN ARE YOU IF DON’T READ THIS AS SHOUTING!?!

Sorry for getting loud there, just trying to make a point. Writing in all caps is widely understood as a way to emphasize what you’re saying, at least if you’re conveying anger or happiness. (McCulloch notes that It doesn’t work the same way for sad messages, for some reason).

For content writers, you have to be careful deploying this one—you don’t want to seem to be screaming at your readers, unless there’s a damn good reason for it. But knowing it’s there as an option may come in handy at certain moments, assuming your clients are OK with a more casual or playful tone of voice.

It should also be noted, context matters for this one too. If your blog post headings are typically all in caps, readers won’t assume they should be read as shouting. Having different formatting alongside the all caps text will signal to them that it’s more of a design choice than a tonal one.

Repeating Letters

Sometimes when dealing with a task that feels tedious and annoying, I’ll message a friend something like “I doooon’t waaaaannnaa do it.” What kind of tone do you read those words in? Probably a tone that sounds a lot like this gif looks.

Repeating letters works as a way to communicate emphasis on certain words. Apparently this use of repeating letters isn’t new with the internet, McCulloch points out that it’s been growing in popularity for over a century, mostly showing up in dialogue in plays and novels before becoming more common in everyday written speech with the internet.

Linguistic research has found that this form of emphasis is more common in private exchanges between people than in public posts, like on social media. So this is a technique you might want to be a little more careful using in your marketing writing, but there may be some contexts where you want to add emphasis without SHOUTING, and repeating letters can help you do that.

Emoji, Gifs, and Memes

You’ve probably been using creative grammar to provide emotional cues to your online writing without thinking about it. But an easier and more obvious way to convey emotion over the internet is to add some images in with the text.

Which brings us to emoji. Whether emoji have a place in your marketing or not depends on your audience and the overall tone you take with your marketing materials. But your audience is almost certainly using them and will know how to recognize and understand common emoji. That makes them a useful option for conveying emotion and tone.

If you write something you mean to be a joke, but that might offend or confuse your audience if they don’t read it as such, an emoji can make sure they understand your intent. If you write something that could come off as confrontational or rude if read in the wrong tone, you can soften it with an emoji. And sometimes emoji can simply help punctuate a point. If you’re describing a cringe moment you want your audience to relate to, the

You’ll likely want to employ emoji more in some marketing contexts than others. They’re a natural fit for the conversational tone of marketing emails and social media, but may seem a little out of place if you try to cram them into more formal business communications like a resume or press release.

Just remember that they can be a valuable communication tool—but only if you know what you’re doing. You don’t want to accidentally slip an eggplant emoji into marketing content where you’re talking about vegetables because, well, that’s not its main use. When in doubt, check Emojipedia to learn about any slang meanings you may want to avoid.

If a static emoji can convey emotion, then a gif that includes a more interactive visual can go even further. But whether to use gifs or reference popular memes in your marketing is a trickier question than emoji. They’re more casual and playful than even emoji are, which will make perfect sense for some brands, but feel really out of place with the overall tone of others.

Gifs often portray actual people, which opens up some additional complications. If you use a seemingly fun gif in an article that features a person who later turns out to be problematic, then future readers of your writing could find themselves faced with the image of an abuser at a point where you’re wanting to convey something fun and light.

Popular memes can be even more fraught for brands to reference. On the one hand, they can be a way to signal to your audience that you understand their references. On the other, if you don’t use them right, they can be a way to show you’re embarrassingly out of touch. Kind of like…well, you know the meme.

That doesn’t mean you should steer clear completely, just that it’s another area where it matters whether you understand the references and memes yourself, or are trying to shoehorn them in for the sake of seeming relatable. Authenticity may be an overused buzzword in a lot of marketing circles, but it matters. It can be the difference between whether meme use in your marketing comes off as clever or cringe.

Understanding the Different Internet Cohorts

The foundation for all good marketing is understanding who you’re talking to. The way you write for the internet—and which trends in internet language to use or not—should always depend on who your audience is and what kind of communication they understand and prefer.

McCulloch breaks down internet users into a few main categories that impact how they communicate online and what kinds of internet language they understand.

- Old Internet People

This is the “founding population” of internet language, the people who remember what McCulloch calls the “old internet.” To be clear, these aren’t necessarily people who are old in years, but those who started using the internet before it became more mainstream. They interacted with people online using tools like Usenet, Internet Relay Chat, and listservs.

These people were using the web when doing so required technological skill, so they’re adept at things like keyboard shortcuts, programming languages, and maybe even computer hardware assembly. Old internet people helped coin some of the internet language that’s now ubiquitous, like “lol” and early use of emoticons before emoji were the easier option.

- Full Internet People

In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, the internet went mainstream. The people who came online during this period (which was a lot of us), tend to fall into one of two categories. The first, full internet people, embraced using the internet socially. They (we) chatted with friends using AOL instant messenger, and had early LiveJournal blogs and MySpace profiles before social media was the dominant cultural force it’s become.

For full internet people, interacting with friends and colleagues online felt (and feels) natural. And internet communication has always included some well known slang (lol, wtf, emoticons, and all caps shouting were already common). This cohort is very comfortable with basic technology, but never had to learn specialized tech skills beyond maybe some basic HTML.

- Semi Internet People

Semi internet people (hi, mom) started using the internet at the same time as full internet people, but they mostly did so for work. They didn’t embrace it as a social tool to the same degree full internet people did. Because of how ubiquitous social media now is, semi internet people are likely to have Facebook accounts now, but came to social media later and aren’t as likely to use the newer, trendier social media platforms of the moment.

They probably have specific technical skills they developed for work, like proficiency with Microsoft Office, but haven’t really dabbled much beyond that. And their typical internet communication is more straightforward than that of other categories. They’ll use and recognize emoji, but are less likely to reference memes or use common internet slang.

- Pre Internet People

Pre internet people are old enough to have been around when full and semi internet people were going online, but they were slow adopters themselves. They put off going online for as long as they thought they could get away with it, but eventually it became a necessity. A lot of pre internet people are older (over 65), but not all.

By now, they have an email account and may have one social media or video chat account a loved one urged them to set up. But using the internet probably never became second nature to them to the way it has to all these other groups. If these people are in your target audience, they may be hard to reach online. This group is less likely to use and understand internet slang—they write online in much the same way that they would write a postcard to a friend. You’re best off avoiding it completely for any marketing targeting pre internet people.

- Post Internet People

Post internet people grew up on the internet. They don’t remember the first time they used a computer, and being social online has always felt like a part of life for them. Post internet people are more likely to be active on platforms their parents aren’t on (what teen wants to interact with friends on Facebook where all your parents, aunts, and uncles can see?).

And they’re pushing the evolution of internet language in ways that won’t be fully understood for a few years. One shift we can recognize now is the evolution of “lol.” The way they use “lol” is no longer about expressing laughter, but more about conveying something about the phrase it’s attached to. It’s used as a way to suggest a second layer of meaning to what you’re saying, which varies depending on context—it could express flirting, a request or offer for empathy, or a softening of expression. If a friend writes you “this project is killing me, lol” they’re not actually suggesting there’s anything funny about the situation. They’re softening the harsh language they used in their complaint, and asking for empathy.

Fun Facts and Tidbits:

- Patterns in language

Linguists are able to find surprising patterns in the way people communicate. Even something like keysmash (something people use to communicate that they’re having feelings so intense they can’t make words—you may have seen it looking like “asdfkfjas;dsfl”) follows recognizable patterns to set it apart from, say, a cat walking across a keyboard. McCulloch points out that intentional keysmash usually starts with a, often “asdf,” and is typically followed by the same characters in various orders (g, h, j, k, l, and ;). In other words, characters from the middle row of the keyboard. In an informal survey of keysmashers, she confirmed that most people will delete and replace their keysmash if it doesn’t look quite right. - The way technology “normalizes” some language (at the expense of others)

Linguists have also found that autocorrect and spellcheck have a discernible impact on the way people write. That’s not entirely a good thing—tools that normalize certain uses of grammar and spelling by presenting them as “right” in comparison to others can slow down the natural evolution of language. And the versions of usage they normalize show bias.

As one example, think about which names spellcheck and autocorrect are most likely to change on a computer or phone in the U.S. Names that come from an English background that tend to be more common amongst white people are more likely to be deemed “correct” by these tools, while names that originated in other parts of the world are more likely to get the little red squiggle or be changed to something else. For writers (and everyone else), it’s worth paying attention to which of these automatic changes and suggestions we accept, instead of going along with all of them. - Text etiquette

People of different generations have developed different norms around texting. Younger people consider it rude to pick up a phone call when hanging out around other people, or for other people to expect them to pick up the phone for an unplanned chat (it interrupts whatever they were doing). Older generations see no issue with taking a call while around other people, they assume it’s important and whoever they’re with will understand. But if someone they’re spending time with starts texting? That looks rude to them. Texting doesn’t seem as important, and shouldn’t they put it off until after you part ways?

This difference in texting etiquette may not apply directly to copywriting, but it’s a good example of how easy it is to offend or upset someone by not understanding how their expectations differ from yours. It pays to be aware of how your audience thinks, so you don’t accidentally violate their idea of etiquette.

Conclusion

Sometimes people who write professionally may feel tempted to push for a specific idea of what writing counts as right or wrong—just think about the regular battles on social around the Oxford comma. But for marketers (and all writers, really), what matters most is making sure your audience can understand what you’re saying. That means a clever reference your audience doesn’t get is wasted, but one they do understand can make them feel more connected to your brand.

It also means that which types of internet language you use should depend entirely on the internet norms of your particular audience. If you’re writing for semi internet people or pre internet people, you should probably ditch the trendy memes and stick with communicating in a more straightforward way. But knowing the way your audience talks online so you can match your language to what they’re used to can be a good way to humanize your brand and write content they connect with.